(This one has nothing to do with zoom lenses…)

This is a picture of me – far left – and four of my schoolmates. It was taken in November 1998 in Market Place, Oakham, Rutland. In the background – and, indeed, the foreground – are some of the cast and crew of the 1999 BBC adaptation of Great Expectations. I was 13 years old when this photo was taken.

This is the only surviving evidence of my one-day career as a television actor.

We were chosen as extras by our drama teacher, whose name was Miss Cushnie. I don’t remember the five of us as a friendship group, but I was very good friends at this point with Tom, second from the left. I can’t remember the others’ names. I think one of them is called Stephen. One of the others might be called Aaron. Nor can I remember who took the picture, but I think Tom’s mum probably took it.

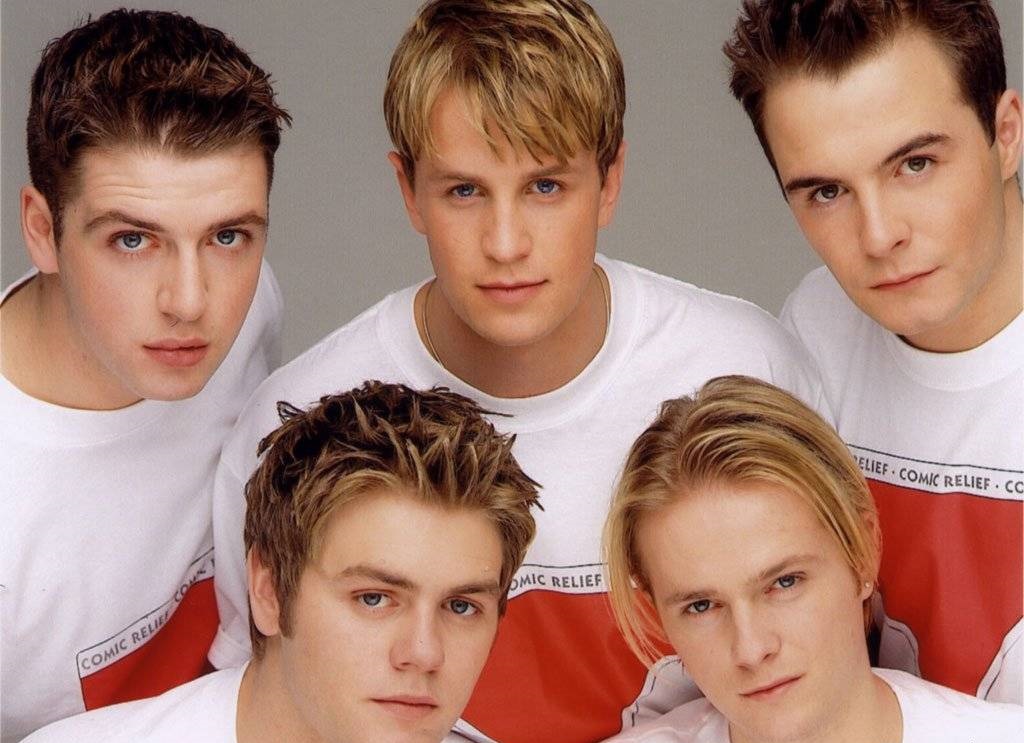

I suppose that casting scouts had approached our school, Vale of Catmose College, to ask for some youths to place apprentices in one of the scenes that was to be shot in the Market Place. We were not selected for any particular dramatic talent. Miss Cushnie chose us because we weren’t anachronistically overweight and we didn’t have anachronistically fashionable haircuts. A fashionable haircut would have been curtains, some form of step or grade, some aspiration towards looking like Boyzone or Westlife.

Westlife, providing five fine examples of non-Dickensian hairstyles

When Miss Cushnie told us that we were going to be “on television” I remember that Tom and I capered around the English quads at school singing “I’m going to be on television, I’m going to be on television” in the style of Eric Cartman in the first season episode “Weight Gain 4000“.

We must have been insufferable. South Park was then brand new, edgy, and at the height of its popularity. Parents were worried about it. They were also worried about Eminem. I wasn’t allowed to watch South Park at home but I remember seeing it for the first time at one of Tom’s birthday parties.

What the Dickens is going on?

[…]

Locations including part of Oakham School, the Buttercross and the Market Place have been chosen to represent lead character Phillip Pirrip’s home village in Kent. Effects including period cladding for buildings and a specially made archway leading to the school have been created to lend atmosphere. Straw will be spread along the ground and part of the market place has been converted into the Blue Boar Inn. Animals will also be used to authenticate the market place scenes.

Leicester Mercury, 19 November 1998, p.34

The production transformed the Market Place, but not as much as one might imagine. The hexagonal structure – the town’s historic buttercross – was barely touched, and the buildings behind them were altered minimally. A structure on the frontage of the building to the right of the buttercross was added by the production, as was shop signage to the left. To the extreme right of the 1998 photograph you can see a large wooden-looking structure. This conceals Oakham’s Post Office, which is a handsome example of GPO architecture, but Not Very Dickensian.

Here’s the picture from 1998 roughly superimposed on a Google Maps Street View image of the same area – which, by happy coincidence, appears to have been taken from roughly the same position:

The production took over a nearby building – which I remember as a scout hut, but it may have been something else – and adjacent car park. The ‘scout hut’ was used as a costume store. On the morning of filming we arrived and were given costumes. I remember very little of the actual process of filming. We stood in a line, each of us youngsters paired up with an older extra. We had to shuffle forward towards a man at a desk who stamped a paper and delivered the line:

The boy is to be bound… bound out of hand

This scene was shot over and over and over again. It was a freezing November morning. I had a cold. It was tremendously boring. I don’t remember having any real aspirations towards an acting career but if I had done, they would surely have been snuffed out. The words “the boy is to be bound… bound out of hand”, however, are burned permanently into my memory.

At lunch we trooped back to the car park and had lunch in a catering services double decker bus: another blow to showbiz glamour. I clearly remember that I ate something very spicy.

Filming took place over two days, but I can’t remember whether I was involved on both days. I think not. All day a large group of local residents assembled at the crash barriers on the perimeter of the set to watch the filming. I think I recall some amusing moments when the animal wranglers chased the geese around.

After 3:30pm the crowds were swelled by students from the independent school close by, and then a little later by the rabble from my more distant secondary school. Lots of girls came to see the filming and I remember hoping that my role in the proceedings might impress them. Unfortunately the real draw was Ioan Gruffudd. The first of ITV’s Hornblower series had been broadcast a month earlier, and Gruffudd was Britain’s newest heartthrob.

Ioan Gruffudd, for whom I was no match

This is the scene we filmed:

Careful scrutiny of this clip, cross-referenced against the photo, reveals the sad truth that I am not visible in the final edit. When I watched the original transmission, in 4:3, I imagined that I’d been in the ‘safe area’ on the margins of the frame; YouTube shows this not to be the case.

Great expections, indeed

At the time of filming, Oakham had high hopes for Great Expectations. A few years earlier the neighbouring town of Stamford had been made rather famous by another BBC television costume drama – Middlemarch. I recall the local newspapers speculating that Oakham would reap a similar tourist dividend.

This is from Leicester Mercury on 19 November, the first day of filming:

Rutland County Council’s economic development officer Sue Bolter says there are big hopes for bringing more visitors to the county when the series is broadcast. […] Ms Bolter said: “I think that although filming can have a slight inconvenience while it’s happening, the longer term pay-off is considerable. “If it’s as successful as Middlemarch was for Stamford it’ll be worthwhile.”

Leicester Mercury, 19 November 1998, p.34

The pay-off never came. In 1994, Stamford became Middlemarch; the town itself was one of the stars of the series. Oakham, it transpired, would feature in a few short scenes of Great Expectations. In addition, Stamford is a delightfully preserved Georgian town with easy access from the A1 and (indirectly) from Kings Cross. Oakham was, and is, neither.

The broader satirical relevance of the South Park episode Weight Gain 4000 probably passed me by at the time:

So, why bother writing all this down? What use are stories like these?

For my own purposes, this is one of the handful of slightly interesting things that have happened to me. It’s a nice bit of personal trivia, and the punchline – that I didn’t “make the cut” – makes it a decent pub anecdote, in a sufficiently desperate conversational lull. Time will tell whether it is up to “something to tell the grandchildren” standard.

If you tilt your head to the left and squint, you may see television production history

The photograph should be of additional use because – behind the show-off group of children – you find a small insight into television drama production practices at a particular moment in the late 1990s. This ought to be useful for the research project I’m currently working on – which is about precisely that sort of history.

Sadly I can remember scarcely any technical details, and with an unfortunate lack of consideration for my future academic career, Tom’s mum focused her camera on her son and his friends, and not on the technology and working practices taking place in the background. We might glean some information about sound recording from that boom microphone in the background; we might also deduce that Puffa-style jackets were en vogue, at least on television film sets on cold November days.

Making and re-making local history

But this doesn’t matter because my underwhelming story of television non-stardom prompts all sorts of memories which are contextually linked to the filming of Great Expectations. In particular, the photograph reminds me that Great Expectations is now woven into the history of Oakham. There must be thousands of people in and from the town who have memories of the filming, or were also involved as extras, or who provided services to the production, or socialised with the crew after shooting was finished for the day.

Even though there was no Middlemarch-effect, seeing Great Expectations as a small part of the history of a small town leads to bigger questions about what television can mean and how television history can be useful. In this case, even the brief descent of a film crew – especially a BBC film crew, and especially one filming a costume drama – can become the talk of a town, and a means of connecting with the town’s real (or imaginary) heritage:

Crowds gathered to watch filming in the Market Place, capturing images to represent young Pip’s home village. […] There was also a flashback for the Market Place when animals, including geese, ducks and horses, were brought in, and straw was scattered to add authenticity to the Dickensian ‘village’.

Leicester Mercury, 20 November 1998, p.11

We also see how these events are later revisited and remembered by rural institutions like the village hall slideshow:

Slides showing last year’s open gardens day in Exton and the filming of Great Expectations in Oakham are to be shown by Irene Kettle at the Fox and Hounds, Exton, on Tuesday, June 20, at 8pm. Entry will be free, but donations and proceeds from a raffle will be given to Rutland and Melton Multiple Sclerosis Society.

Leicester Mercury, 16 June 2000, p.30

Examples like these help to make the point that television history isn’t just about remembering the programmes or production practices of the past; nor is digitizing archives merely a question of enabling people to watch old television programmes. It can also be a way of bringing local history to life, and of prompting memories which are only tangentially related to television itself.

Local television news archives are obvious stores of local and family history (will genealogists of the future find their great-great-grandfather in an East Midlands Today news bulletin?) but we shouldn’t forget the importance of appearances, however fleeting, in programmes of other genres. Every location shoot is a moment in local history.